Science News

We all know plants need nutrients, especially nitrogen and phosphorus. To give crops a boost, they are often put on fields as fertilizer. But we never talk about where the nutrients themselves come from. Phosphorus, for example, is taken from the Earth, and in just 100-250 years, we could be facing a terrible shortage. That is, unless scientists can find ways to recycle it.

Cotton breeders face a “Catch-22.” Yield from cotton crops is inversely related to fiber quality. In general, as yield improves, fiber quality decreases, and vice-versa. “This is one of the most significant challenges for cotton breeders,” says Peng Chee, a researcher at the University of Georgia.

We’ve all heard about the magical combination of being in the right place at the right time. Well for fertilizer, it’s more accurate to say it should be in the right place at the right rate. A group of Canadian scientists wanted to find the perfect combination for farmers in their northern prairies.

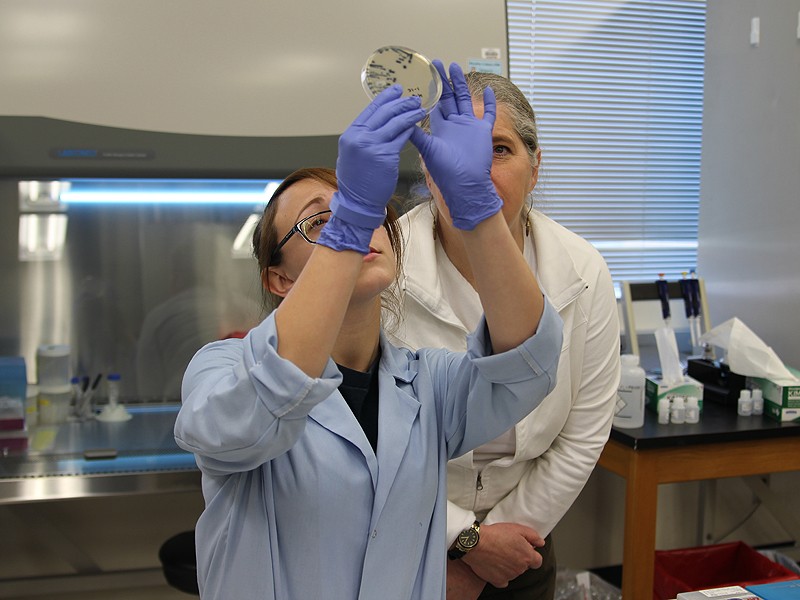

It’s not fun when a fungus contaminates crops. Safe native fungi, however, show promise in the fight against toxic fungal contamination.

Crops just can’t do without phosphorus.

Globally, more than 45 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer are expected to be used in 2019. But only a fraction of the added phosphorus will end up being available to crops.

The impact is two-fold: financial and environmental. “Fertilizer costs are significant for farmers in south Florida,” says Tiedeman. “And phosphorus rock, the most widely used source of phosphorus fertilizer, is in low supply across the globe. It is thought that phosphorus rock resources will only be available for the next 50 to 200 years.”

Salads were recently in the news—and off America’s dinner tables—when romaine lettuce was recalled nationwide. Outbreaks of intestinal illness were traced to romaine lettuce contaminated with Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria.

These bacteria occur naturally in the intestines of warm-blooded animals. Because crops are grown in the natural environment, E.coli may get into the fields, contaminating produce. The results are potentially deadly for people who eat that produce.

“A healthy community requires healthy soil.” This idea spurred a consortium of researchers, farmers, and community garden practitioners to dive into the challenges—and opportunities—of urban agriculture. Their efforts, now in a second year, may highlight how urban soil can be a resource for human and environmental health.

Farmers irrigating their crops may soon be getting some help from space. In 2018, scientists launched ECOSTRESS, a new instrument now attached to the International Space Station. Its mission: to gather data on how plants use water across the world.

The ECOsystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station (ECOSTRESS) helps scientists answer three broad questions:

Soils all over the Earth’s surface are rigorously tested and managed. But what about soils that are down in the murky depths? Although not traditional soils, underwater soils have value and function. Some scientists are working to get them the recognition and research they deserve.

One of these scientists is Mark Stolt from the University of Rhode Island. He and his team are working to sample and map underwater soils.

The plant world works in mysterious ways. We often think of plants producing flowers so those flowers can produce seeds for the next generation. But what would be the purpose of a flower that doesn’t bear seeds?

“We were particularly perplexed as to why a plant would invest energy if that structure isn't making a seed,” says Elizabeth Kellogg. “It seems as though it would be a waste of energy.”