Natural Resources

Plants need water—but what about when it’s running low? Is it possible to use less water and still have healthy crops?

A ditch containing woodchips may look unassuming—but with a name like bioreactor it’s guaranteed to be up to more than you think.

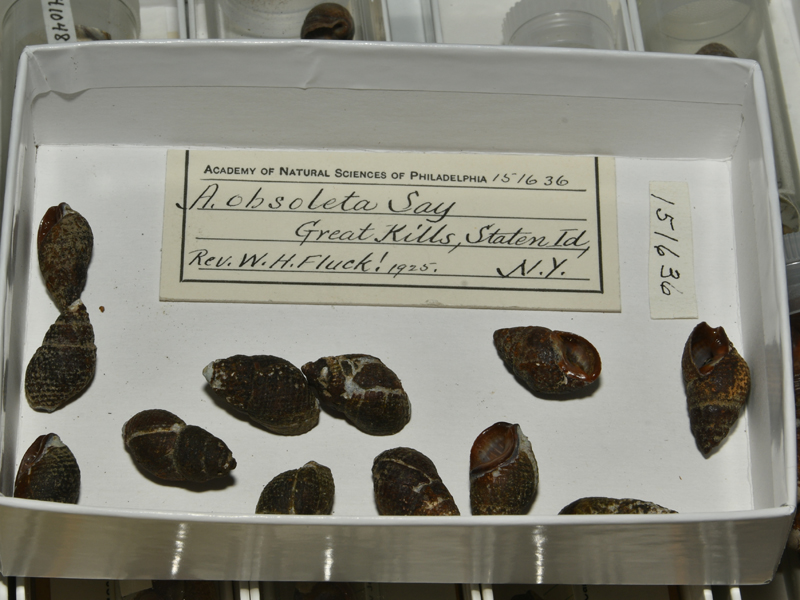

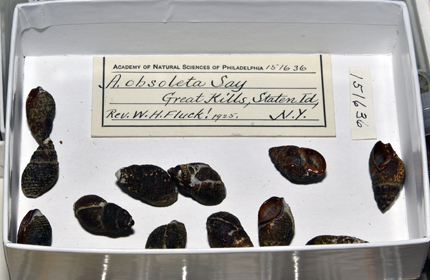

A tiny snail could be a big help to researchers measuring water quality along the U.S. and Canadian Atlantic coast.

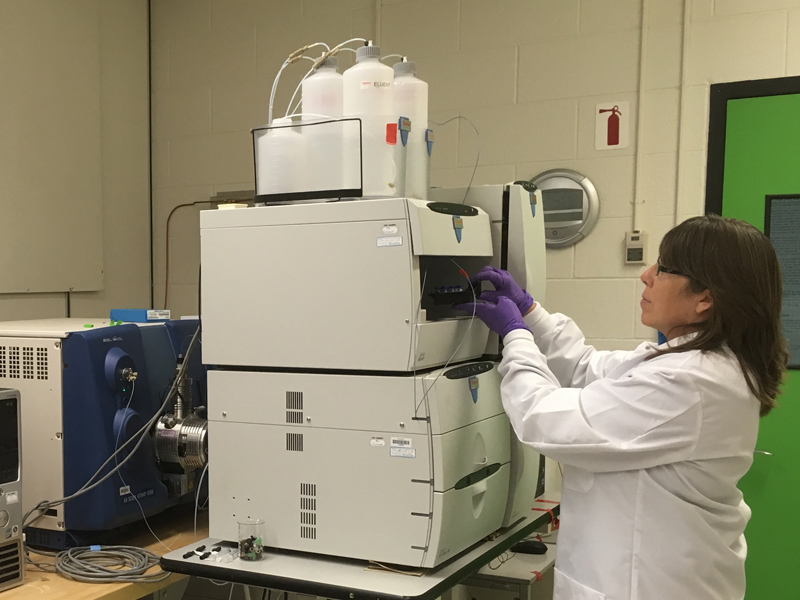

We often “flush it and forget it” when it comes to waste from toilets and sinks. However, it’s important to be able to track this wastewater to ensure it doesn’t end up in unwanted places. A group of Canadian scientists has found an unlikely solution.

Ecologist Lindsey Rustad sculpts ice forests. She’s not a sculptor by trade, but in her latest ecology experiment, her team sprayed water over a portion of forest during the coldest part of the night. Within hours, the water froze to the branches, simulating an ice storm.

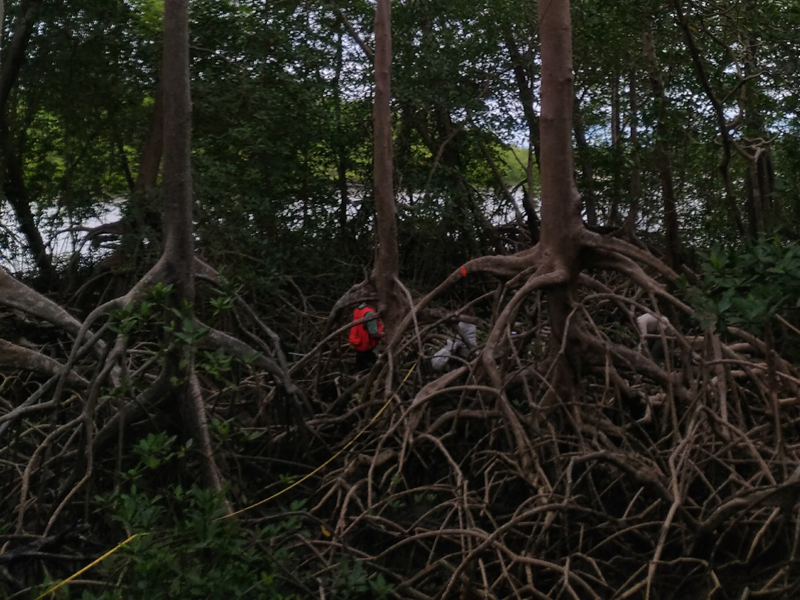

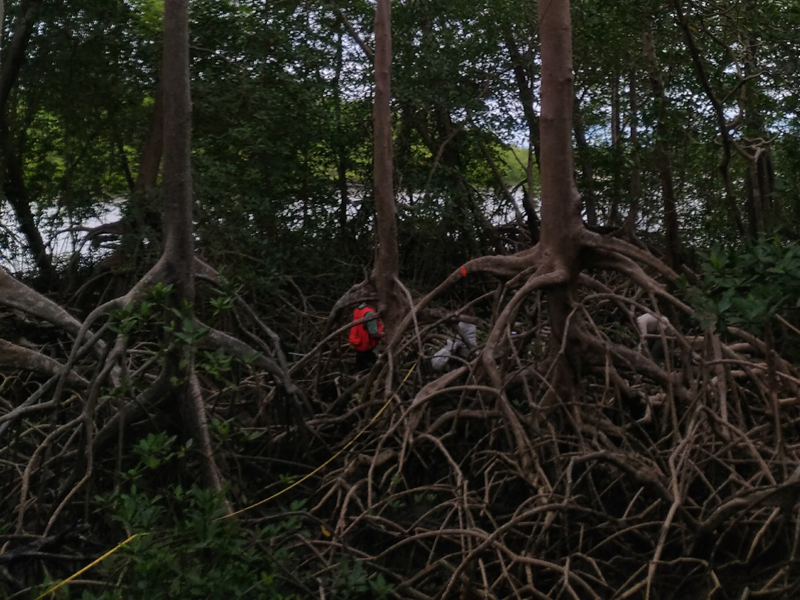

Did you know carbon comes in blue?

Blue carbon refers to the carbon in oceans and coastal areas. These ecosystems are excellent carbon sinks – they can efficiently absorb and store carbon from the atmosphere.

Blue carbon refers to the carbon in oceans and coastal areas. These ecosystems are excellent carbon sinks – they can efficiently absorb and store carbon from the atmosphere.

And with global emissions of carbon dioxide topping 35 billion tons in 2016, carbon sinks are more important than ever.

Nitrogen can present a dilemma for farmers and land managers.

On one hand, it is an essential nutrient for crops.

The Lower Mississippi River Basin’s Delta region lies mainly in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. It is a fertile area that produces many crops. The region is warm and humid, with plenty of water. This makes it a potentially important carbon sink, capable of absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. However, such warm soil and plentiful moisture can also have the opposite effect. Carbon dioxide is released from decaying plants and organic matter in the soil.

Huckleberry Finn wouldn’t recognize today’s lower Mississippi River. Massive walls separate the river from low-lying lands along the bank, an area called the floodplain. Floodplains were once the spillover zone for the river. As people settled in floodplains, the land was converted into farms, homes, and businesses. Close to 1,700 miles of walls, or levees, keep the lower Mississippi River in check.

Less than a mile from the edge of the bustling Penn State University campus lies 600 acres of cropland and forests crisscrossed with irrigation pipes. The water being pumped out of these pipes isn’t channeled from a river or a well. Instead, over 500 million gallons of treated wastewater from the campus is discharged at this site every year.