Soil Science Society of America

5585 Guilford Road • Madison, WI 53711-5801 • 608-273-8080 • Fax 608-273-2021

www.soils.org

Twitter | Facebook

NEWS RELEASE

Contact: Hanna Jeske, Associate Director of Marketing and Brand Strategy, 608-268-3972, hjeske@sciencesocieties.org

Plant genetic resources ensure ag’s future

Sept. 26, 2018 - Imagine a gardener, plant explorer, geneticist, and computer specialist all rolled into one job. You might call that person a steward of plant genetic resources.

Plant genetic resources are any plant materials, such as seeds, fruits, cuttings, pollen, and other organs and tissues from which plants can be grown. The stewards are the breeders, researchers, farmers, genebank staff, and many others who keep them safe and utilize them.

Plant genetic resources are any plant materials, such as seeds, fruits, cuttings, pollen, and other organs and tissues from which plants can be grown. The stewards are the breeders, researchers, farmers, genebank staff, and many others who keep them safe and utilize them.

Peter Bretting, a National Program Leader for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, says these plant genetic materials and those who care for them are important for human survival.

“These are the materials for crop breeding which play a role in food security and plant research,” he says. “Crops make up the thin green line standing between humanity and calamity. To feed the growing world population, breeders must develop new crop types that yield more on less land with less materials such as water and fertilizer.”

To do this, crops must have new genetic materials that enable them to produce more food. The materials for this are conserved and provided to stewards who keep safe the future of agriculture and humanity’s survival, Bretting adds.

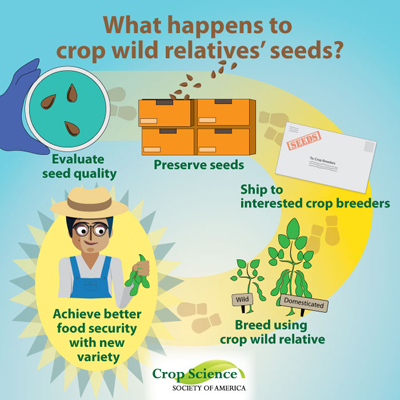

An important part of these plant genetic resources is crop wild relatives. These are closely related to crop species but have not been domesticated by humans. They are often related to crops eaten today in some way and provide useful material for breeding, study, and preservation, says Bretting.

For example, breeders might find they want a trait like drought tolerance in a specific crop. It may be a rare quality only found in an ancestor. Luckily, breeders might be able to find what they need thanks to the stewards who are conserving the wild ancestors.

For example, breeders might find they want a trait like drought tolerance in a specific crop. It may be a rare quality only found in an ancestor. Luckily, breeders might be able to find what they need thanks to the stewards who are conserving the wild ancestors.

“Historically, plant genetic resource stewardship had focused on taking care of domesticated crop species,” Bretting says. “Because of this, there have been fewer crop wild relatives in genebank collections than there should be, and not well-protected in nature. Thus, new plant genetic resource stewards must specifically try to safeguard crop wild relatives.”

Plant genetic resources are carefully collected and stored. They are collected from the field in the form of seeds, fruits, bulbs, tubers, pollen, young plants, or cuttings. They are often selected to fill in gaps and make sure a collection covers as many plant types as possible.

Storing the plant genetic resources can take many forms. After drying, most are stored in cold or dry conditions. Depending on what they need, storage temperatures may vary between 41°F and -138°F (5°C and -150°C).

However, some cannot be kept in this way. Those must be constantly maintained as plants in field orchards or greenhouse plantings.

“Plant genetic resources are often distributed from genebanks as materials for breeding programs and as subjects of research,” he says. “Requests for plant genetic resources can include seeds, fruits, bulbs, tubers, vegetative cuttings, or young plants. They are then used in crop breeding, research, and, in the end, agricultural production.”

Bretting says the future of plant genetic resources and their stewards is bright and filled with new technologies. Areas like artificial intelligence could continue to improve how they collect, store, and conserve this important resource. He adds that the people behind this work are the key to its success and should be celebrated.

Bretting says the future of plant genetic resources and their stewards is bright and filled with new technologies. Areas like artificial intelligence could continue to improve how they collect, store, and conserve this important resource. He adds that the people behind this work are the key to its success and should be celebrated.

“Their devotion, often for decades, to conserving and providing plant genetic resources is wonderful,” he says. “They often develop state-of-the-art solutions to seemingly impossible challenges. They and plant breeders serve as the ‘first responders’ to new crop diseases, pests, environmental extremes, and human-caused disruptions which could harm food security.”

Read more about this work in Crop Science. Bretting received CSSA’s 2017 Frank Meyer Medal for Plant Genetic Resources.

To learn more about crop wild relatives, visit this page, Crop Wild Relative Week. There, you will find a collection of web stories, blogs, a video, and infographics explaining the importance of these wild relatives to our food security. CSSA celebrates Crop Wild Relative Week annually, September 22-29, with 2018 being the inaugural year.

Crop Scienceis the flagship journal of the Crop Science Society of America. It is a top international journal in the fields of crop breeding and genetics, crop physiology, and crop production. The journal is a critical outlet for articles describing plant germplasm collections and their use.